Over the past few months two different readers have contacted me to ask about the question of punctuation in Matthew 24:5, specifically about the quotation marks usually found there. I have written a fair amount on this blog about the lack of punctuation in Ancient Greek, including quotation marks, and this has spawned a fair amount of discussion. Part of that discussion has taken place off-line since it did not directly address the semantics or syntax of Ancient Greek, but issues of interpretation.

It turns out, though, that this quotation in Matthew 24:5 is a great example of why you need to understand the semantics, syntax, and patterns of usage for Ancient Greek in order to make valid determinations about punctuation.

It is not a matter of deciding where quotation marks could work in English. There are limits on what could count as a quote, and where that quote could start or end imposed by the meanings of the Greek words involved, their grammatical forms, and the wider context of what is being said.

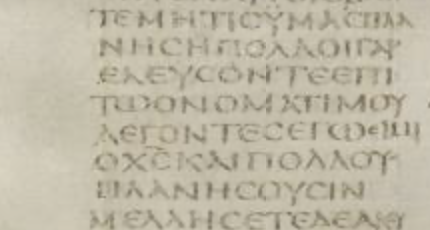

In this particular case, the text is as follows:

πολλοὶ γὰρ ἐλεύσονται ἐπὶ τῷ ὀνόματί μου λέγοντες

Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ Χριστός, καὶ πολλοὺς πλανήσουσιν.

The first part is pretty simple: πολλοὶ γὰρ ἐλεύσονται ἐπὶ τῷ ὀνόματί μου (For many will come in my name). The following participle (λέγοντες) introduces what those coming in Jesus’ name will say: Ἐγώ εἰμι ὁ Χριστός. It is the people who say this that will lead many astray (καὶ πολλοὺς πλανήσουσιν).

The two people who inquired about this verse both asked if it could be read without quotation marks altogether, rendering a meaning quite different from what is usually found in published translations. If there is no quote here, so the argument goes, then Ἐγώ could refer to Jesus, and not to the false teachers who he says will come later. That is, they asked if the text could be read as saying

Many will come in my name saying I am the Messiah, and they will lead many astray.

While this may seem plausible in English, it is not plausible in Greek. In English we can say “Many will come in my name saying I am…” and understand “my” and “I” to refer to the same person. In Greek, though, the form of the statement would likely be quite different if ἐγώ and μου referred to the same person. We would be far more likely to see something like this:

πολλοὶ γὰρ ἐλεύσονται ἐπὶ τῷ ὀνόματί μου λέγοντες

ἐμέ εἰναι τὸν Χριστόν, καὶ πολλοὺς πλανήσουσιν.

That is, if no quotation were involved, the usual wording in Greek would involve expressing the part about who is the Messiah with an infinitival clause, with both its subject and object expressed in the accusative case.

If Matthew intended us to understand that Jesus was saying the false teachers would acknowledge him as the messiah, he chose an extremely confusing way to say it. His first readers would certainly read what he wrote to mean the false teachers would claim to be the messiah, not that they would acknowledge him in that role.

Despite the lack of punctuation in the Ancient Greek texts, it is problematic to decide about the punctuation of a translation on the basis of what works in English. A familiarity with the structure of Ancient Greek and the usual patterns of expression in that language are essential for making such decisions.

I appreciate the questions posed by readers of my comments on punctuation. While I don’t always have a quick answer, they inevitably send me back to the text to look for the limits and possibilities offered by the ancient authors’ choices of wording.

For further reading on the issue of punctuation in Ancient Greek, see the following posts:

I would like to give a special thank you to Shelia Harrison and Serge Beugels for prompting me to take a fresh look at this passage. Thank you for your curiosity and critical thinking!