I recently had the opportunity to provide professional development (PD) to all of the principals in a local school system. The objective of the PD was to make them aware of the experience of newcomers in their schools—students who arrive in the US understanding no English—and demonstrate ways teachers need to be adapting instruction for them. The school system has roughly 1,300 English Language Learners, and 240 of those are newcomers.

I gave the principals a taste of what it is like to understand nothing of what is being said to you, then showed them what their teachers need to do to help these students acquire English. To accomplish this, I addressed them in Ancient Greek and conducted the first 20 minutes or so of the professional development only in Ancient Greek.

For our purposes here at Greek-Language.com, what I did illustrates what we need to do to teach Ancient Greek in Greek. For the principals in this training, it was to help them see the scope of the need for solid English instruction.

We started the session with my colleague, Jessica Tallant instructing the participants to close their laptops. We did this for two reasons: first, to keep them focussed on the Ancient Greek lesson that was about to begin, but that they did not know about, and second, because near the end of the upcoming lesson I would instruct them in Greek to open their laptops. This would be a quick way to see who was understanding and who was not.

I began by reading aloud α Greek text which includes a set of instructions for beginning a brief assignment based on that text (see εἰκὼν α).

Of course they understood nothing and were unable to follow the instructions. I repeated them more slowly. When no one began to work on the assignment, I repeated the instruction a third time, this time slowly and louder.

Unfortunately, this is all some teachers know to do to “help” newcomers complete their schoolwork in English, and I wanted to demonstrate clearly the futility of this.

Jessica then led the principals in a brief discussion in English of what they had just experienced and whether they thought they could learn Greek this way. They quickly made the connection to their students and the need to do more than speak slowly and loudly if we want them to learn English.

I then told the participants that we would read the Greek text again, but this time I would “scaffold it” for them so that they could understand. Again, I displayed the text, but this time the first word was highlighted in red, and there was an illustration to help understand it (εἰκὼν β).

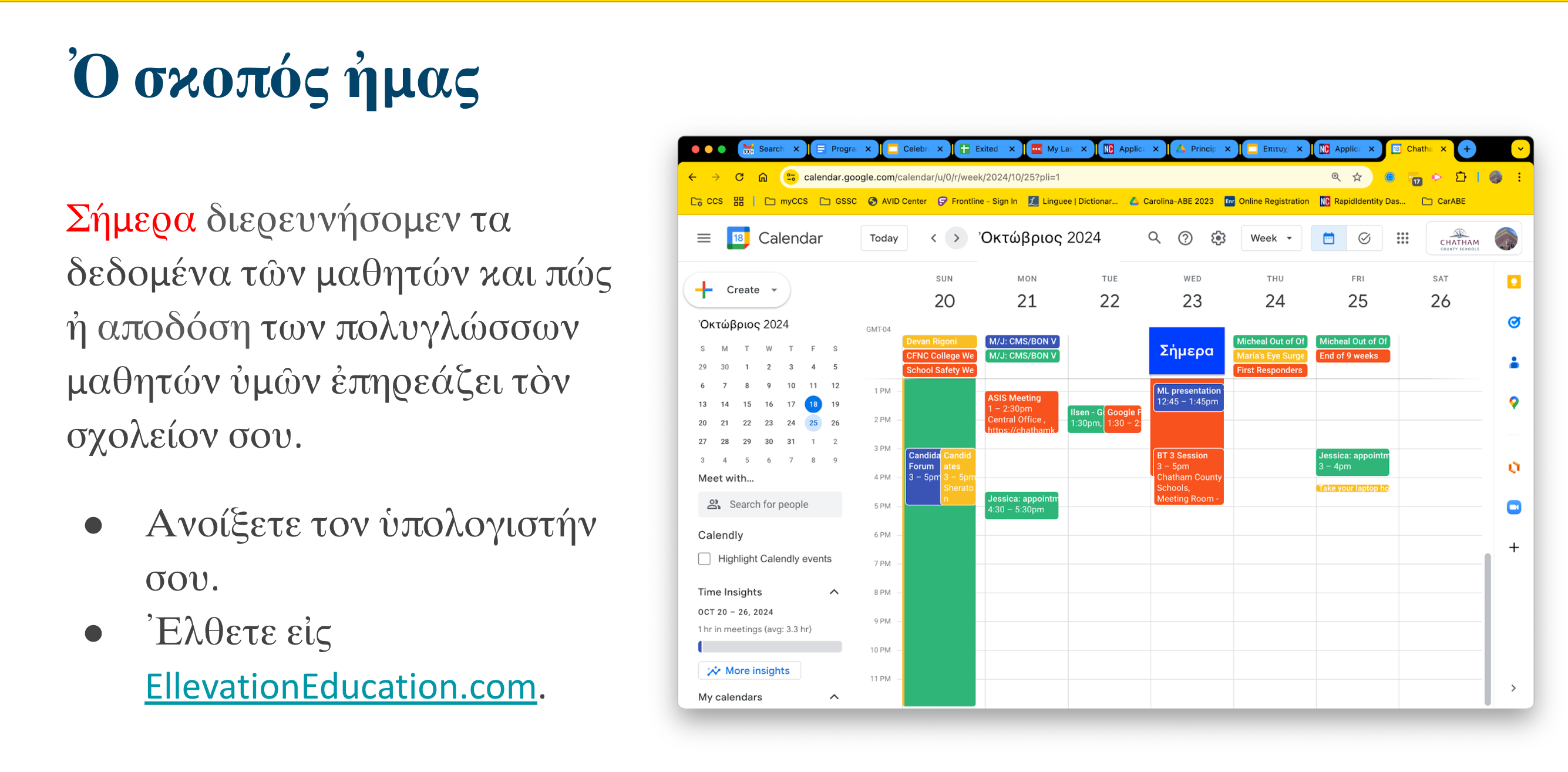

Signaling the image of a Google Calendar page, I said Σήμερα as I pointed to October 23 (the day of the PD) and to the word Σήμερα that I had added to the calendar above the date.

Next I pointed to the highlighted word in the Greek text and again said Σήμερα.

Pointing to the calendar again I said Σήμερα, είκοσι τρίτο τοῦ ᾽Οκτωβρίου, illustrating Σήμερα” with the American Sign Language sign for “today” and illustrating είκοσι τρίτο with two fingers then three (23). I did this twice, then I repeated είκοσι τρίτο τοῦ ᾽Οκτωβρίου as I pointed first at the number 23, then to the word Ὀκτώβριος above the month.

Finally, I pointed again to the first word of the Greek text and said: σήμερα.

On the next slide (εἰκὼν γ) the word διερευνήσομεν was highlighted, and there was in illustration of a woman looking through an oversized set of binoculars.

Pointing to the first two words of the text, I said Σήμερα διερευνήσομεν, illustrating σήμερα with the sign for “today” and using my hands to make pretend binoculars. I looked around the crowd as if examining them.

Pointing to myself, I said διερευνήσω (still with the pretend binoculars. Pointing to the crowed I said διερευνήσετε. Pointing to both myself and the crowd, I said διερευνήσομεν.

Pointing to the first two words of the text, I repeated Σήμερα διερευνήσομεν, illustrating σήμερα with the sign, and διερευνήσομεν with the binoculars gesture.

The next slide (εἰκὼν δ) repeated the same Greek text, but with the words τὰ δεδομένα highlighted in red and illustrated by three examples of data. Pointing to the highlighted words, I read aloud, τὰ δεδομένα. Then, indicating the illustration, I repeated the phrase. Pointing to each example of data one at a time, I said δεδομένα, and pointing to the beginning of the text, I read aloud, Σήμερα διερευνήσομεν τὰ δεδομένα.

The next slide (εἰκὼν ε) highlighted the words τῶν μαθητών. Once again I read the highlighted words aloud, then pointing to the picture of four school children I repeated τῶν μαθητών. Next I pointed to each student individually and said μαθητής. Then I moved my hand from the first student to the last as I repeated, τῶν μαθητών. I read the beginning of the text aloud again, Σήμερα διερευνήσομεν τὰ δεδομένα τῶν μαθητών.

At this point I heard one of the principals say softly, “We’re going to look at our student data.”

On the next slide I skipped the words καὶ πώς since understanding those words would not increase the likelihood of success for the participants.

Showing an illustration of two students with contrasting work (one strong, one weak), I read aloud the highlighted words on the next slide: ἡ αποδόση (εἰκὼν ζ). Pointing to the passing grade I said αποδόση καλή (giving a hearty thumbs up). Then I pointed to the failing grade and said αποδόση κακή (giving a thumbs down with a frown).

Next I pointed to both papers and repeated, ἡ αποδόση.

In this brief section I had adapted the modern Demotic Greek word απόδοση (performance, yield) and treated it as if it were Ancient Greek. (Note, for example, the change in the accented syllable to reflect the pattern prevalent in the Hellenistic Period). I guess I could have used καρπός, but it just didn’t feel right in this context. If you know an Ancient Greek word that would fit well here, suggest it in the comments, and I’ll use it next time!

At this point, the slide updated to place a label above each student. Pointing to the strong student in the illustration, I said “δυνατός μαθητής” (flexing my biceps). Then I pointed to her work saying, αποδόση καλή (with thumbs up), and I added: Ὀι δυνατοί μαθηταί (pointing to the label) ποιοῦσιν ἀποδόσην καλήν (pointing to the student’s paper).

I pointed to the second student saying “ἀδύναμος μαθητής” (while frowning and drooping my shoulders). Signaling her work, I repeated αποδόση κακή (with a thumbs down sign), and added: Ὀι ἀδύνατοι μαθηταί (pointing to the label) ποιοῦσιν ἀποδόσην κακήν (pointing to the student’s paper).

I briefly reviewed the meaning of τῶν μαθητών by showing an image of a teacher with her students.

Pointing to the students in the picture I said, μαθητοί. Then I pointed to their teacher and said said, οὶ μαθητοὶ αὐτής.

Reading from the text again (ἡ αποδόση τῶν μαθητών ὐμῶν) I emphasized the word ὐμών as I pointed to the audience.

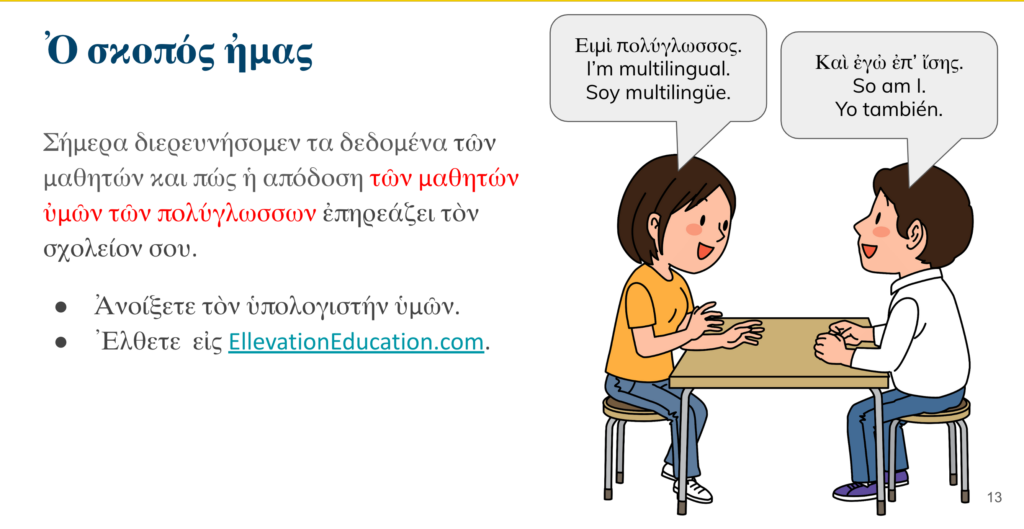

Next I read aloud ἡ αποδόση τῶν μαθητών ὐμῶν τῶν πολυγλώσσων. Displaying an illustration of two multilingual students (εἰκὼν ι), I held up two fingers, and said Δύο μαθηταί πολύγλωσσοι.

Pointing to the girl’s speech bubble, I counted the languages: ἕν, δύο, τρεῖς, and said μαθητής πολυγλώσση. Next I pointed to the boy’s speech bubble and counted the languages: ἕν, δύο, τρεῖς, and added, μαθητής πολύγλωσσος. Then I repeated μαθηταί πολύγλωσσοι (moving my index finger from one student to the other).

Once again reading from the text, I said ἡ αποδόση τῶν μαθητών ὐμῶν τῶν πολυγλώσσων, illustrating τῶν μαθητών ὐμῶν τῶν πολυγλώσσων as I read.

The next slide highlighted the words ἐπηρεάζει τὸν σχολείον.

Σχολεῖον was not the usual way of referring to a school in Hellenistic Greek, but it came to be used that way not long after, and I decided to use it because our English word “school” derives from this Greek root. It would make the work of the students (principals) a bit easier.

Running my finger under the words ἡ αποδόση τῶν μαθητών ὐμῶν τῶν πολυγλώσσων, I read the words aloud, then paused briefly before reading the words highlighted in red on the next slide: ἐπηρεάζει τον σχολείον σου (εἰκὼν κ).

Pointing to the upper image of students, I said, οἱ δυνατοί μαθηταί αἴρουσι τὸν σκολίον (raising my palms under the school on the opposite side of the upper scale.

Then pointing to the lower image of students, I said, οἱ ἀδύνατοι μαθηταί κατεβάλλουσι τον σχολείον (pointing to the school and pretending the push it down).

The next slide displayed the text again, with the instruction Ἀνοίξετε τὸν ὑπολογιστήν σου highlighted.

Making the open book sign, I said, Ανοίξετε τον υπολογιστήν σου. I pointed to the illustration and said ὑπολογιστήν, then repeated the instruction: Ανοίξετε τον ὑπολογιστήν σου. All of the principals promptly opened their laptops.

I then pointed to the second bulleted instruction and said Ἔλθετε εἰς Ἐλλεβατιὸν Ἐδυκατιὸν τελεία κομ. Most of the principals immediately started typing the URL. The rest took their cue from those around them and did the same.

Giving them a few seconds to get to the correct website. I asked in English, “Are you all at EllevationEducation.com?” They were.

At this point I turned the meetινγ back over to Jessica, who led them in a productive discussion of what they understood the Greek text to mean, and how they had been able to follow the instructions.

Our objectives had been to get them to follow the instructions AND to have a rough understanding of what the entire Greek text said. While their understanding of the text was not perfect, it was gratifyingly accurate given that this was the first time any of them had studied Ancient Greek. They understood that the passage indicated we would examine our student data, and that the performance of multilingual learners impacts the performance of the entire school. They correctly identified the scaffolding techniques I had used to convey this meaning and to enable them to follow the directions.

What does this mean for us at Greek-Langauge.com?

This experience demonstrates clearly that students who have no previous understanding of Ancient Greek can follow along, understanding a rather complex text, and following instructions, if the teaching incorporates strong enough support to enable understanding.

When I told my wife about this experience, she raised an obvious question, “Were they really understanding the Greek, or just your gestures and the images?” This is a valid question, and it deserves a careful, well supported response.

My day job is to administer a language acquisition program for a medium sized school district in North Carolina. Equipping teachers to succeed at teaching English has given me a wealth of experience watching successful language instruction at work. That experience confirms what research on the topic has firmly established: If students consistently comprehend what is said to them, meeting lesson objectives in the language of instruction, they will acquire the language in which the receive that instruction.

Getting students to successfully follow along understanding what they hear, will implant the language of instruction in their brains. Of course they will not be able to speak the language at first, but they will begin the process of acquiring the language, not just learning about it.

Language acquisition is the process by which we develop the ability to both understand and produce language, primarily through exposure to spoken language in our environment, where we naturally absorb sounds, patterns, and meanings, gradually expanding our vocabulary and building grammar skills. Speech comprehension precedes speech production. Our ability to understand what we hear is always slightly ahead of our ability to speak. By enabling comprehension, we lay the groundwork for emerging speaking ability.

With our first language, we learn to understand and speak long before we begin the process of becoming literate. We learn to read and write only after becoming orally fluent.

Authentic reading comprehension in a second or third language is also dependent upon oral language comprehension. When studying modern languages we learn to comprehend what is said to us, speaking the language, and learning to read and write it all at the same time. Sometimes our reading ability may even slightly outpace our oral comprehension, but the two remain tightly connected.

Students who are not orally fluent struggle terribly to learn to read in English. Increasing their oral fluency enables higher levels of literacy. Similarly, teaching Ancient Greek through reading alone creates limits comprehension. If we can develop methods to acquire oral fluency in Ancient Greek, we will enable higher levels of reading comprehension, removing the barriers that are naturally present when trying to read without the oral language foundation to support literacy.

I am not orally fluent in Ancient Greek. I had to prepare and rehearse to be able to conduct the lesson described above, but witnessing the success of the “students” on October 23 confirms that what I do to support modern language acquisition, can and does work when applied to an ancient one. We can teach Greek beginning with the oral language, and when we do it well, comprehension will follow. It’s hard work, but if my experience as a modern language acquisition specialist is any indication, doing so will benefit not only the students.

Good teachers progress faster than their students. If you want to become fluent in Ancient Greek, start preparing to teach Ancient Greek in Greek.

For further reading

Shawn Loewen, Introduction to Instructed Second Language Acquisition, Routledge, 2020.

Kirsten M. Hummel, Introducing Second Language Acquisition, Wilie-Blackwell, 2021