Originally published on January 6, 2013

This morning I heard Peter Carman preach on Matthew 2:1-12. He did a super job, striking a great balance between scholarship and pastoral guidance.

As the scriptural text was being read aloud in English, I followed along in my Greek text. [Yes. I am one of those geeks who takes the Greek text to church. I don’t use it to intimidate other worshipers but because I find reading the Greek texts to be a meaningful experience.] As I was reading this text, it hit me that it’s a great example of the problem posed by the lack of clear indication of where quotes begin and end in Ancient Greek.

While it’s usually very easy to see where a quote begins, finding the end of the quote is much more challenging because there was no punctuation, and no grammatical convention, to indicate this. The particular point at which the issue appears in this text is in the priests’ and scribes’ response to Herod when he asks them about where the Christ will be born.

Ηρῴδης . . . συναγαγὼν πάντας τοὺς ἀρχιερεῖς καὶ γραμματεῖς τοῦ λαοῦ ἐπυνθάνετο παρ᾿ αὐτῶν ποῦ ὁ χριστὸς γεννᾶται (verses 3 and 4).

Herod . . . gathering all the high priests and scribes of the people, inquired of them concerning where the Christ would be born.

The clause introducing their response is quite clear:

οἱ δὲ εἶπαν αὐτῷ·. . .

And they said to him: . . .

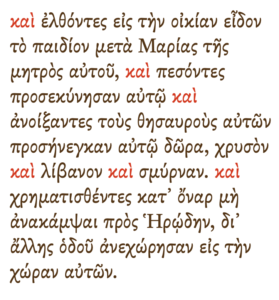

So it’s not hard to find the beginning of the quote. Where we decide the quote ends, though, has a significant impact on the meaning of the passage. The NRSV, NIV, NET Bible, and TEV all use quotation marks to have the response include all of the following:

ἐν Βηθλέεμ τῆς Ἰουδαίας· οὕτως γὰρ γέγραπται διὰ τοῦ προφήτου· 6 καὶ σὺ Βηθλέεμ, γῆ Ἰούδα, οὐδαμῶς ἐλαχίστη εἶ ἐν τοῖς ἡγεμόσιν Ἰούδα· ἐκ σοῦ γὰρ ἐξελεύσεται ἡγούμενος, ὅστις ποιμανεῖ τὸν λαόν μου τὸν Ἰσραήλ. (verses 5 and 6)

In Bethlehem of Judea, for thus it has been written by the prophet: ‘And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah, for from you will come a ruler who is to shepherd my people Israel.”

This interpretive decision is perfectly reasonable, of course, but it is not the only one possible, and it does have significance for what Matthew intended. It asserts that the chief priests and scribes quoted scripture to Herod. While there is no clear reason to think they wouldn’t do this, it’s also not clear that Matthew meant us to understand the text in this way.

Let’s consider another option that is equally well supported by the the text. Suppose Matthew meant only that they answered, ἐν Βηθλέεμ τῆς Ἰουδαίας (in Bethlehem of Judea).

Keep in mind that the raised dot in the printed text further above is an editor’s decision based on evidence that first appeared in the text much later than its date of composition. A period is an equally reasonable interpretation of that same evidence.

If the author of this text intended the quote to include nothing more than ἐν Βηθλέεμ τῆς Ἰουδαίας, then the rest of this section would be his own attempt to explain why they gave this answer.

οὕτως γὰρ γέγραπται διὰ τοῦ προφήτου· 6 καὶ σὺ Βηθλέεμ, γῆ Ἰούδα, οὐδαμῶς ἐλαχίστη εἶ ἐν τοῖς ἡγεμόσιν Ἰούδα· ἐκ σοῦ γὰρ ἐξελεύσεται ἡγούμενος, ὅστις ποιμανεῖ τὸν λαόν μου τὸν Ἰσραήλ.

For thus it has been written by the prophet: “And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who is to shepherd my people Israel.”

In this reading of the text, the scriptural quote does not represent something the high priests and scribes said to Herod, but something the author quoted to his readers to show the significance of the answer given by the high priests and scribes to Herod’s question.

I apologize to Peter for thinking about this while he was delivering his insightful sermon this morning. While he didn’t discuss the punctuation of the text, he did make me think a lot about the text’s significance for today’s church. For that I thank him seriously.

Here’s a little reflection on why we should care about the punctuation:

Punctuation matters. When I mentioned this issue to my 16-year-old daughter earlier this afternoon, she responded, “Of course punctuation matters. ‘Let’s eat, Grandma’ doesn’t mean the same as ‘Let’s eat Grandma.'” She’s right, of course. It matters.

For a competent reader of Ancient Greek to fail to question the punctuation in our printed editions of the Ancient Greek texts is an abdication of a significant part of our responsibility. If we don’t struggle with the punctuation, we are simply handing that responsibility off to the editors of those texts. While that is a reasonable thing for students early in the study of the language to do, it is not a reasonable thing for accomplished readers to do. Question the punctuation. Struggle with it. Ask how the text would change if we punctuated it differently. What options are reasonable? Which ones are not? This is a part of what it means to read seriously.

Here are some other posts dealing with the lack of punctuation in Ancient Greek:

There is also one tangentially related topic that arose out of this discussion earlier:

Happy reading!

Important! [Added Jan. 19, 2015]:

While the earliest manuscripts of the biblical texts did not contain punctuation, it is usually clear to a competent reader of Ancient Greek where the punctuation belongs.

It is a serious mistake to assume that the absence of punctuation in those manuscripts means a person who does not read Greek is free to choose where to put the punctuation in an English translation. To make decisions about where the punctuation belongs, it is necessary to read Ancient Greek very well. Many options that would seem to be available in an English text are ruled out by the structure of the Greek text.

Earlier today, Eric Rasmusen posted the following comment in the Punctuation in Ancient Greek Texts discussion. While his comment is related to that topic, it raises a question more specific to the usage of

Earlier today, Eric Rasmusen posted the following comment in the Punctuation in Ancient Greek Texts discussion. While his comment is related to that topic, it raises a question more specific to the usage of